You may or may not have heard of deep seabed mining, but recently it has been causing a stir amongst scientists, ocean conservationists and environmental activists alike. All agree that deep seabed mining should be avoided, at least until we can adequately study the ecosystems that live on the sea floor to determine whether or not this industry will have a devastating effect on our oceans and, if so, how we could mitigate that risk.

“Allowing deep-sea mining would mean the deep ocean will be exploited before it is explored,” – Edith Widder, marine biologist.

So, what is down there on the seabed?

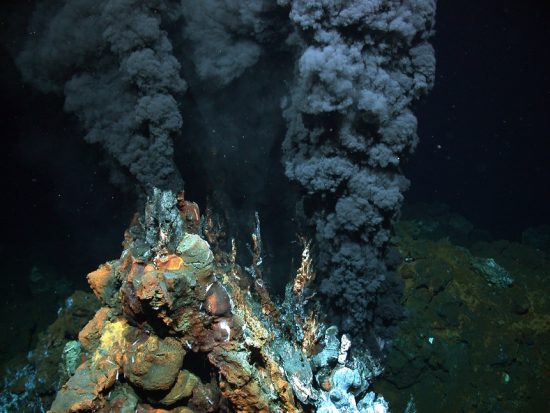

Oceanography is still a relatively new field of science and travelling to the deepest of sea floors is an expensive and dangerous process, but there has been enough exploration to mark some unexpected yet crucial biological discoveries. In 1977 a US-funded submersible, Alvin, found deep-sea vents off the coast of the Galápagos islands, Ecuador.

These vents were home to an ancient ecosystem with large organisms such as 3-metre-long tube worms, as well as crabs, shrimps and mussels, all dependant on the colonies of bacteria that survive by a process known as chemosynthesis. Chemosynthesis differs from photosynthesis in that it doesn’t involve converting sunlight to energy. Instead, the bacteria living on deep-sea hydrothermal vents derive their energy from hydrogen sulphides, compounds that are toxic to humans and other land-dwelling organisms.

These unique but fragile ecosystems have been thought by scientists to have been the source of complex life on earth, and since bacteria are what helped to form cells as we know them, and earth’s surface was at that time almost entirely underwater yet lacked much of the oxygen we have today, it makes perfect sense.

These revelations came with further discoveries – hydrothermal vents also regulate the chemistry of the ocean and transport heat from under the sea floor into the water column, creating a vital circulatory system which spreads heat and minerals across the vast oceans and therefore maintains the delicate balance of chemicals and salts that most life on earth depends on.

But what is deep seabed mining?

The minerals that are deposited by deep-sea hydrothermal vents are rare and valuable to humans due to our insatiable appetite for electronic gadgets, such as tablets and smart phones.

Hydrothermal vents are the source of manganese nodules and are also rich in other metals and minerals like cobalt, platinum, silver, copper, gold and zinc. Cobalt is widely used for making lithium-ion batteries, manganese is mostly applied to desulfurize and deoxidize steel in steel production, and zinc is a transition metal used for galvanizing steel and iron. Other mined metals and minerals are also considered profitable for various purposes.

Deep seabed mining is the process of harvesting these minerals by effectively ploughing the sea floor and destroying entire ecosystems, most of which may never recover.

Do we really need to mine the sea floor?

Some governments and industries prefer the idea of deep seabed mining for minerals, because it means they may no longer be publicly contributing to slave labour, political corruption, contamination of water and destruction of ecosystems. Instead, they will be able to the very same things in relative privacy of the open ocean- devastating marine ecosystems, polluting the ocean, putting their crew at risk and hiding the profits.

For developing nations, however, these resources are liquid gold mines, and if they are denied access then they could turn to other destructive industries such as fishing or drilling for oil and gas to make up their profits.

The most obvious alternative to mining the sea floor would be to recycle the minerals we have already used – from batteries, for example – as this would not only prevent the need to mine but also reduce the volume of toxic waste we throw into landfills or natural bodies of water.

Who will profit from deep seabed mining?

This is a very important question, because as we are all aware most wealth is not distributed evenly. What we can do is look at similar industries and make an educated guess. For example, BP Shell discovered huge crude oil reserves in Nigeria in 1956, and until the 1990’s the British made the majority of profits. However, even after a deal was finally agreed upon, corruption within the industry and government prevented the lucrative oil profits from reaching Nigeria’s masses, and despite the value of their natural resources Nigeria remains high in poverty and low in socioeconomic equality.

When considering minerals on our seabed we have a much more complicated ownership definition. At a country or territory’s borders, all water within 12 miles of the coastline is considered jurisdictional. Beyond that, maritime laws apply, but these laws were written before we discovered that we could potentially profit from deep sea thermal vents. Expect governments and privatised industry to blur the lines of ownership and stewardship when it comes to the exploitation of nature for financial or political gain.

What kind of damage can deep seabed mining cause?

Currently, we know that the methods proposed for deep sea mining will very likely destroy most structures, natural or manmade, in its path. Our knowledge of the deep sea, especially hydrothermal vents, is very limited because sadly our governments have not invested much in scientific exploration (or conservation) of the ocean, but the evidence we do have clearly suggests that disturbance to these ecosystems may not be reversible.

When compared to space exploration, marine science has had access to 1% of the funding allocated for exploration and research, despite the fact that we have yet to map the sea floors and as a species we have effectively only just breached the surface of our vast oceans.

The scientific research that exists suggests that the living ecosystems on and around hydrothermal vents are potentially the oldest living ecosystems on our planet and have survived previous climate fluctuations and natural disasters. It appears the main and ever impending threat towards these ancient habitats is human activity, of which some are intentional and some merely collateral damage.

A German-funded experiment from 1988 to 1997, in which an area in Peru rich in manganese nodules was deliberately destroyed for research purposes, showed that recovery was likely to be painfully slow and human mining of such an ecosystem may have permanent devastating effects.

What can we do to stop it?

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) and the IUCN hold authority over member states on decisions such as deep sea mining, but there are actions we can take individually to protect our ocean habitats.

Click here to SIGN THIS PETITION to stop deep seabed mining

AND you can:

- Let your local government representative know that they have your support to end deep sea mining.

- Talk to your colleagues, friends and family about deep seabed mining and share what information you know.

- Write to industry leaders, such as Apple, Tesla and Samsung, to let them know you won’t purchase products that contain minerals derived from deep sea vents.

- Share information on social media, and tag companies and government bodies.

- Reduce the volume of lithium batteries that you purchase, Recycle what you no longer need and Refrain from dumping old batteries into household waste!

What we also need to do is increase awareness and funding for the development of better and cheaper technologies to mine our landfills and recycle the minerals that we have harvested in our smart phones, batteries and other electronic gadgets. Without these innovations we will be fighting a losing battle as our dependency for these rare minerals grows and our capacity to find alternative solutions diminishes.

The technological revolution is far from over, and some argue it has only just begun. There will be more efficient, affordable and renewable options for energy storage in the foreseeable time to come. What we need to do is demand that it comes sooner rather than later.

Recent Developments:

In September 2021 the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) held a conference for the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to review the regulations for deep seabed mining after several governments and contractors had requested a two-year permit that would allow them to mine for minerals.

The final votes were held in favour of a moratorium (temporary suspension) of mining activities in the deep sea, with thousands of votes from diplomats, scientists and conservationists.

This great news, however, brings with it a lingering warning of what may be to come in the mineral mining industry, as access to resources is limited and recycling what we do have access to could be laborious and expensive. It’s ultimately up to us as consumers and citizens to exercise our rights to support a kinder and more sustainable economic future.

Link to Petition:

https://www.change.org/p/international-seabed-authority-stop-deep-sea-mining

Sources include:

https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/international-seabed-authority-and-deep-seabed-mining

https://www.whoi.edu/feature/history-hydrothermal-vents/impacts/index.html

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1742-6596/1582/1/012098/meta

https://chinadialogueocean.net/6682-future-deep-seabed-mining/

https://search.schlowlibrary.org/Record/311858/TOC

https://www.iucncongress2020.org/motion/069

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.631.7721&rep=rep1&type=pdf